What we know today

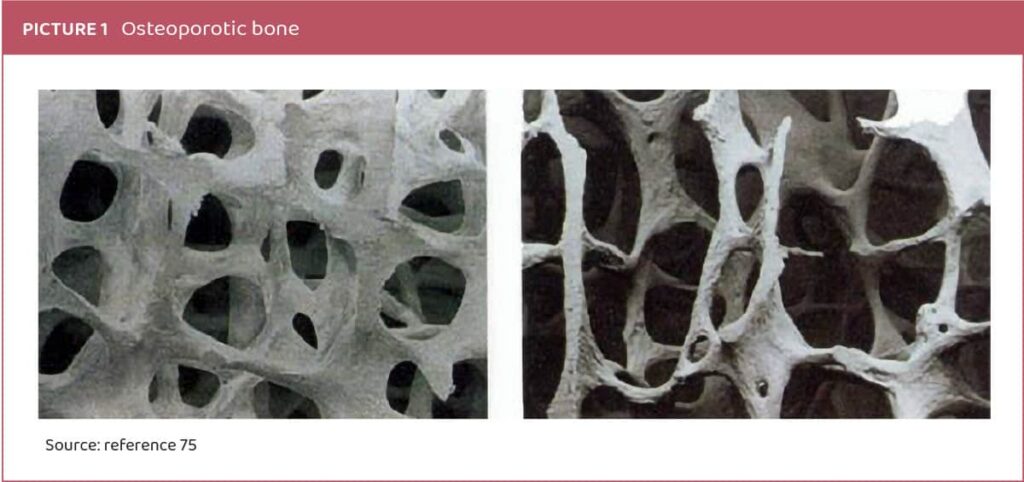

Osteoporosis, characterized by progressive loss of bone mass and deterioration of bone tissue structure, particularly microstructure, is a prevalent skeletal disease affecting over 200 million individuals worldwide, posing a significant global public health concern (Picture 1). Fractures associated with osteoporosis stem from increased bone fragility and susceptibility to fractures. The principal pathophysiological mechanism involves an imbalance in bone remodeling, with heightened bone resorption by osteoclasts and decreased bone formation by osteoblasts, resulting in continuous bone loss, typically observed as a decline in bone mineral density (BMD) at a rate of approximately 2-5% per year, along with deterioration in bone microarchitecture.1-4

Osteoporosis can be classified as primary (type I), occurring as a natural part of aging, particularly in women with estrogen deficiency post-menopause, or secondary (senile) osteoporosis, resulting from medical conditions, diseases, or certain medical treatments. The multifactorial development of primary osteoporosis involves genetic and environmental factors, including diet, lifestyle choices (such as smoking), hygiene practices, and antibiotic use.5-7

New findings

Given the high incidence and prevalence of osteoporosis and osteopenia worldwide, the scientific community continues its pursuit of effective and safe treatment options.8 Presently, therapeutic choices remain limited, with lifestyle modifications showing low compliance rates.9 While hormonal estrogen therapy, such as red clover isoflavone supplementation, has demonstrated effectiveness in prevention and treatment, it’s associated with severe adverse events.11 Similarly, antiresorptive agents like bisphosphonates, parathyroid hormone, and calcitonin face limited use due to adverse effects, high costs, and poor compliance.12 Although calcium and vitamin D offer beneficial effects on bone microarchitecture and overall bone health, they’re insufficient alone for treating menopausal bone loss.13 Current treatment methods typically involve a combination of lifestyle adjustments, bone health supplements, drug intervention, and rehabilitation.

The gut microbiome’s role in osteoporosis has emerged as a significant area of research.14 Studies indicate that the gut microbiome influences osteoclast and osteoblast activity through metabolite secretion, impacting host metabolism and immune response.15,16 Dysbiosis-induced gastrointestinal inflammation and disturbances in metabolite secretion can lead to potent osteoclastogenic cytokine production, contributing to bone loss. Moreover, the gut microbiome affects the intestinal absorption of minerals crucial for bone health.17,18 Imbalances in the gut microbiome, along with estrogen deficiency, can increase gut permeability, facilitating the absorption of toxins and pathogens, thus promoting systemic inflammation detrimental to bone turnover.

The complexity and time-dependent nature of the gut microbiome’s effects on bone health are evident in research. This has led to the emergence of the term “osteomicrobiology” to describe research on the gut microbiome’s impact on bone health and metabolic bone diseases.19,20

Probiotics, live microorganisms with beneficial health effects for the host, offer a promising avenue for osteoporosis treatment.21 However, not all probiotics are equally effective due to differences in food processing, strain specificity, and targeted effects. Probiotics likely exert their effects through modulation of gut microbiome metabolite secretion, influencing immune response, and improving gut epithelial barrier function, crucial for normal bone cell functioning.22,23 While the magnitude of probiotic treatment’s effect may be lower compared to anti-resorptive drugs, it’s comparable to calcium and/or vitamin D treatment.25

The discovery that probiotics can mitigate bone mass loss presents a novel approach to osteoporosis prevention and treatment.26 In vitro studies reveal that different probiotic strains have varying effects on bone health, indicating both cell-specific and strain-specific mechanisms. For instance, Lactobacillus reuteri has been shown to inhibit osteoclast differentiation and reverse TNF-a-induced suppression of Wnt10b expression, potentially through histamine secretion.27 Similarly, Lactobacillus casei 393 and Lactobacillus helveticus have demonstrated effects on bone cell proliferation and osteoblast differentiation, respectively, suggesting strain-specific interactions with bone metabolism.30

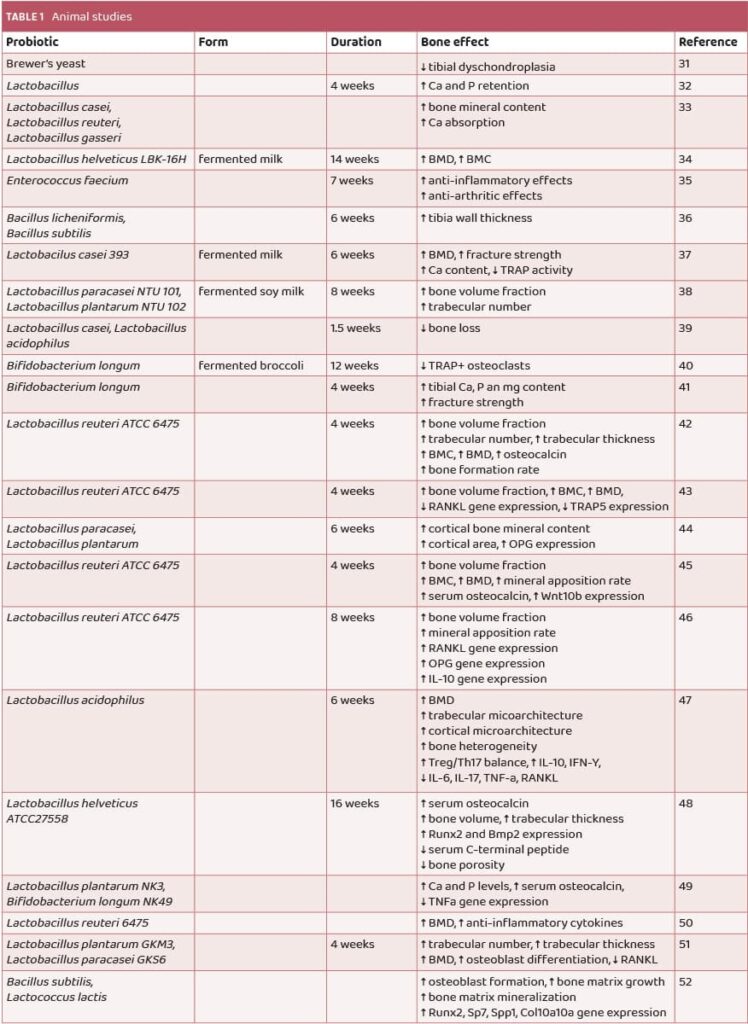

Studies in animals have shown probiotic supplementation to improve BMD and have osteoprotective properties in osteoporosis. Results of several studies are shown in Table 1.

In a study by Amdekar et al. in 2012, supplementation with the probiotics Lactobacillus casei and Lactobacillus acidophilus demonstrated an osteoprotective effect, reducing bone loss caused by oxidative stress through their anti-oxidative mechanism of action.37 Additionally, results from Rodrigues et al. showed intriguing findings, indicating that supplementation with Bifidobacterium longum ATCC15707 for 28 days increased the calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium content in the tibias of male rats, along with higher fracture strength compared to controls41 (Table 1). Furthermore, a study by Parvaneh et al. found that probiotic supplementation with Bifidobacterium longum increased bone density, trabecular thickness, and number, as well as femoral strength. This was achieved by elevating serum osteocalcin levels, promoting osteoblast genesis and bone formation parameters, while simultaneously decreasing osteoclast activity over the bone surface in the femur and reducing C-terminal telopeptide levels between ovariectomized and sham-ovariectomized mice48 (Table 1).

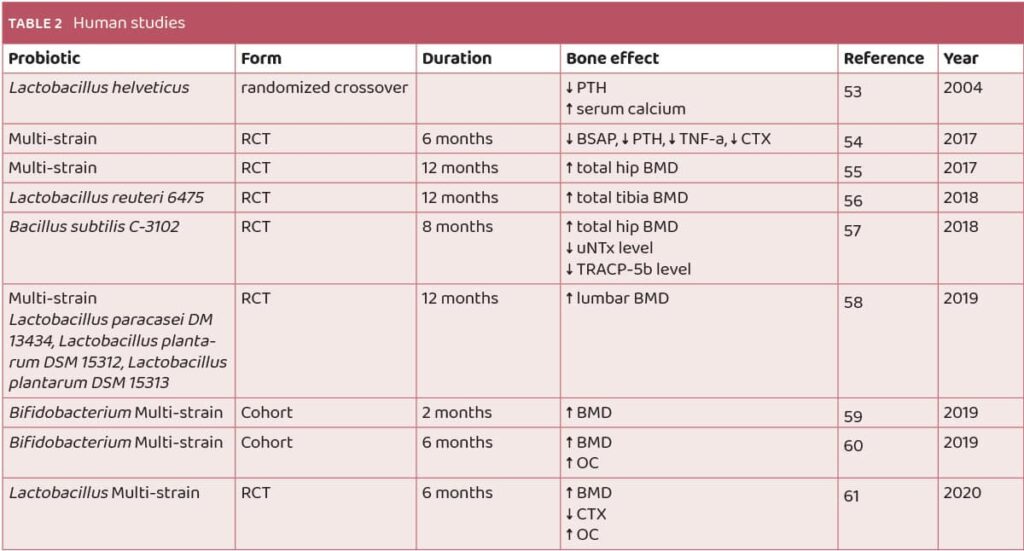

Positive results were seen in studies on humans too. The list of human studies on probiotics and osteoporosis are summarized in Table 2.

In a study by Narva et al., probiotic supplementation was found to decrease serum parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels while increasing serum calcium levels. Notably, this effect was observed only when the probiotic itself was administered, not when solely peptides secreted by the probiotic were applied53 (Table 2). Conversely, research by Jafarnejad et al. demonstrated that probiotic supplementation led to a decrease in bone-specific alkaline phosphatase levels, parathyroid hormone, tumor necrosis factor TNF-a, and collagen type 1 cross-linked C-telopeptide. However, spine and hip bone mineral density (BMD) remained unaffected by probiotic supplementation54 (Table 2).

Mechanisms of action

Probiotics exert their influence on bone health through various mechanisms.

The primary mechanism involves the positive alteration of gut microbiota composition by probiotics, leading to an optimal profile of gut microbiome metabolite secretion with systemic benefits to the host, including bone metabolism.62,63,64

Probiotics can enhance the utilization of calcium, phosphorus, and iron, as well as the absorption of iron and vitamin D, through the secretion of metabolites such as lactic, butyric, and acetic acid.65

Certain probiotics have been found to increase the expression of the vitamin D receptor (VDR) in both humans and animal studies, thereby increasing circulating vitamin D levels, which suggests that probiotics can enhance the positive effect of vitamin D on bone health through multiple pathways.66

Additionally, probiotic administration can lead to altered hormone levels, such as estrogen, which plays a crucial role in the pathophysiology of osteoporosis.67

By influencing gut microbiome metabolite secretion, probiotics can reduce intestinal pH, leading to increased calcium solubility and absorption in the intestinal lumen, ultimately resulting in increased bone mineral content and density. This mechanism is particularly important in the elderly population where intestinal absorption is often diminished.

Another significant mechanism of probiotics in osteoporosis involves their anti-inflammatory effects. Probiotics can mitigate the inflammatory cascade impacting bone turnover by calming gastrointestinal and systemic inflammation and producing anti-inflammatory metabolites, such as arginine deiminase in the case of Lactobacillus brevis CD2. Probiotics may also reduce the expression of proinflammatory and osteolytic cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interferon 17 (IL-17), and receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa ligand (RANKL), resulting in reduced osteoclast formation and enhanced osteoblastic activity. Furthermore, the anti-inflammatory effect of probiotics improves calcium transport across the intestinal barrier.68,69

Moreover, probiotics can influence the expression of genes crucial for bone metabolism, rendering them as antioxidants by enhancing bone cell response to oxidative stress, which is heightened in estrogen deficiency and leads to increased osteoclast over osteoblast differentiation.39

Probiotic trials for osteoporosis

Research on the effects of probiotic supplementation on bone health has yielded promising results, indicating potential benefits for individuals at risk of osteoporosis. Clinical trials involving both humans and animals have highlighted the positive impact of certain probiotic strains such as L. reuteri, L. casei, L. paracasei, L. bulgaricus, L. acidophilus, and B. subtilis.70 For instance, in a study involving osteopenic postmenopausal women, a 12-week regimen of multispecies probiotics was found to potentially slow the increase in serum bone resorption marker CTX, suggesting a mechanism for reducing osteoclast-induced bone resorption without adverse effects.71 Another study observed that supplementation with probiotics containing L. reuteri 6475 over the course of a year led to a significant reduction in bone loss (osteoporosis) in women.72 This indicates a potential long-term benefit in preserving bone health. Animal studies have also provided insights, showing that strains like Lactobacillus casei, L. reuteri, L. gasseri, and B. longum (ATCC 15707) can enhance bone mineral density, calcium absorption, and fracture strength.73, 74

These findings collectively suggest that probiotic supplementation could offer a natural approach to support bone health, potentially reducing the risk of osteoporosis. However, further research, particularly randomized controlled trials with larger cohorts, is necessary to validate these findings and establish optimal dosage and duration for probiotic interventions targeting bone health.

Conclusions

The gut microbiome and the host immune response play critical roles in the pathophysiology of osteoporosis. Probiotics offer osteoprotective benefits by positively influencing the gut microbiome and modulating the host immune response through various direct and indirect mechanisms. Research across in vitro, animal, and human studies has demonstrated the beneficial effects of probiotic administration on bone health and osteoporosis. However, further investigation is warranted to delve into the strain-specific mechanisms of action, particularly concerning the gut microbiome and metabolite secretion. This emphasizes the potential of probiotics as adjunctive therapeutic agents in the prevention and management of osteoporosis, while underscoring the need for continued research to elucidate their precise mechanisms of action.

References:

- Mitlak BH, Nussbaum SR. 1993. Diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis. Annu Rev Med. 44:265-277.

- Pouresmaeili F, Kamalidehghan B, Kamarehei M, Goh YM. 2018. A comprehensive overview on osteoporosis and its risk factors. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 14:2029-2049.

- aring B, Crandall CJ, Wu C, LeBlanc ES, Shikany JM, Carbone L, Orchard T, Thomas F, Wactawaski-Wende J, Li W et al. 2016. Dietary patterns and fractures in postmenopausal women: Results from the women’s health initiative. JAMA Intern Med. 176(5):645-652.

- Finkelstein JS, Brockwell SE, Mehta V, Greendale GA, Sowers MR, Ettinger B, Lo JC, Johnston JM, Cauley JA, Danielson ME et al. 2008. Bone mineral density changes during the menopause transition in a multiethnic cohort of women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 93(3):861-868.

- Bliuc D, Nguyen ND, Alarkawi D, Nguyen TV, Eisman JA, Center JR. 2015. Accelerated bone loss and increased post-fracture mortality in elderly women and men. Osteoporos Int. 26(4):1331-1339.

- Kerschan-Schindl K. 2016. Prevention and rehabilitation of osteoporosis. Wien Med Wochenschr. 166(1-2):22-27.

- Muhammad A, Mada SB, Malami I, Forcados GE, Erukainure OL, Sani H, Abubakar IB. 2018. Postmenopausal osteoporosis and breast cancer: The biochemical links and beneficial effects of functional foods. Biomed Pharmacother. 107:571-582.

- Black DM, Rosen CJ. 2016. Clinical practice. Postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 374(3):254-262.

- Häuselmann HJ, Rizzoli R. 2003. A comprehensive review of treatments for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 14(1):2-12.

- Simin J, Tamimi R, Lagergren J, Adami HO, Brusselaers N. 2017. Menopausal hormone therapy and cancer risk: An overestimated risk? Eur J Cancer. 84:60-68.

- Boonen S, Vanderschueren D, Haentjens P, Lips P. 2006. Calcium and vitamin d in the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis – a clinical update. J Intern Med. 259(6):539-552.

- Yang CY, Chen CH, Wang HY, Hsiao HL, Hsiao YH, Chung WH. 2014. Strontium ranelate related stevens-johnson syndrome: A case report. Osteoporos Int. 25(6):1813-1816.

- Gonnelli S, Cepollaro C, Pondrelli C, Martini S, Montagnani A, Monaco R, Gennari C. 1999. Bone turnover and the response to alendronate treatment in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int. 65(5):359-364.

- Ohlsson C, Sjögren K. 2015. Effects of the gut microbiota on bone mass. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 26(2):69-74.

- Yano JM, Yu K, Donaldson GP, Shastri GG, Ann P, Ma L, Nagler CR, Ismagilov RF, Mazmanian SK, Hsiao EY. 2015. Indigenous bacteria from the gut microbiota regulate host serotonin biosynthesis. Cell. 161(2):264-276.

- Yadav VK, Ryu JH, Suda N, Tanaka KF, Gingrich JA, Schütz G, Glorieux FH, Chiang CY, Zajac JD, Insogna KL et al. 2008. Lrp5 controls bone formation by inhibiting serotonin synthesis in the duodenum. Cell. 135(5):825-837.

- Collins KH, Paul HA, Reimer RA, Seerattan RA, Hart DA, Herzog W. 2015. Relationship between inflammation, the gut microbiota, and metabolic osteoarthritis development: Studies in a rat model. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 23(11):1989-1998.

- Ali T, Lam D, Bronze MS, Humphrey MB. 2009. Osteoporosis in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Med. 122(7):599-604.

- Yan J, Herzog JW, Tsang K, Brennan CA, Bower MA, Garrett WS, Sartor BR, Aliprantis AO, Charles JF. 2016. Gut microbiota induce igf-1 and promote bone formation and growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 113(47):E7554-e7563.

- Ohlsson C, Sjögren K. 2018. Osteomicrobiology: A new cross-disciplinary research field. Calcif Tissue Int. 102(4):426-432.

- Gibson GR, Hutkins R, Sanders ME, Prescott SL, Reimer RA, Salminen SJ, Scott K, Stanton C, Swanson KS, Cani PD et al. 2017. Expert consensus document: The international scientific association for probiotics and prebiotics (isapp) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 14(8):491-502.

- iver E, Berenbaum F, Valdes AM, Araujo de Carvalho I, Bindels LB, Brandi ML, Calder PC, Castronovo V, Cavalier E, Cherubini A et al. 2019. Gut microbiota and osteoarthritis management: An expert consensus of the european society for clinical and economic aspects of osteoporosis, osteoarthritis and musculoskeletal diseases (esceo). Ageing Res Rev. 55:100946.

- Zhong Y, Zheng C, Zheng JH, Xu SC. 2020. The relationship between intestinal flora changes and osteoporosis in rats with inflammatory bowel disease and the improvement effect of probiotics. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 24(10):5697-5702.

- Dar HY, Azam Z, Anupam R, Mondal RK, Srivastava RK. 2018a. Osteoimmunology: The nexus between bone and immune system. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 23(3):464-492.

- Biver E, Berenbaum F, Valdes AM, Araujo de Carvalho I, Bindels LB, Brandi ML, Calder PC, Castronovo V, Cavalier E, Cherubini A et al. 2019. Gut microbiota and osteoarthritis management: An expert consensus of the european society for clinical and economic aspects of osteoporosis, osteoarthritis and musculoskeletal diseases (esceo). Ageing Res Rev. 55:100946.

- Britton RA, Irwin R, Quach D, Schaefer L, Zhang J, Lee T, Parameswaran N, McCabe LR. 2014. Probiotic l. Reuteri treatment prevents bone loss in a menopausal ovariectomized mouse model. J Cell Physiol. 229(11):1822-1830.

- Zhang J, Motyl KJ, Irwin R, MacDougald OA, Britton RA, McCabe LR. 2015. Loss of bone and wnt10b expression in male type 1 diabetic mice is blocked by the probiotic lactobacillus reuteri. Endocrinology. 156(9):3169-3182.

- homas CM, Hong T, van Pijkeren JP, Hemarajata P, Trinh DV, Hu W, Britton RA, Kalkum M, Versalovic J. 2012. Histamine derived from probiotic lactobacillus reuteri suppresses tnf via modulation of pka and erk signaling. PLoS One. 7(2):e31951.

- Kim DE, Kim JK, Han SK, Jang SE, Han MJ, Kim DH. 2019. Lactobacillus plantarum nk3 and bifidobacterium longum nk49 alleviate bacterial vaginosis and osteoporosis in mice by suppressing nf-κb-linked tnf-α expression. J Med Food. 22(10):1022-1031.

- Narva M, Collin M, Lamberg-Allardt C, Kärkkäinen M, Poussa T, Vapaatalo H, Korpela R. 2004. Effects of long-term intervention with lactobacillus helveticus-fermented milk on bone mineral density and bone mineral content in growing rats. Ann Nutr Metab. 48(4):228-234.

- I. PLAVNIK, M.L. SCOTT (1980) Effects of Additional Vitamins, Minerals, or Brewer’s Yeast upon Leg Weaknesses in Broiler Chicken. Poultry Science. 59: 459-464

- Nahashon SN, Nakaue HS, Mirosh LW. Production variables and nutrient retention in single comb White Leghorn laying pullets fed diets supplemented with direct-fed microbials. Poult Sci. 1994 Nov;73(11):1699-711

- Ghanem, K.Z. & Badawy, I.H. & Abdel-Salam, Ahmed. (2004). Influence of yoghurt and probiotic yoghurt on the absorption of calcium, magnesium, iron and bone mineralization in rats. Milchwissenschaft. 59. 472-475.

- Narva M, Nevala R, Poussa T, Korpela R. The effect of Lactobacillus helveticus fermented milk on acute changes in calcium metabolism in postmenopausal women. Eur J Nutr. 2004 Apr;43(2):61-8. doi: 10.1007/s00394-004-0441-y.

- Rovensky, Josef & Švík, Karol & Matha, Vladimir & Istok, Richard & Ebringer, Ladislav & Ferencík, Miroslav & Stancikova, Maria. (2004). The effects of Enterococcus faecium and selenium on methotrexate treatment in rat adjuvant-induced arthritis. Clinical & developmental immunology. 11. 267-73.

- Mutuş R, Kocabagli N, Alp M, Acar N, Eren M, Gezen SS. The effect of dietary probiotic supplementation on tibial bone characteristics and strength in broilers. Poult Sci. 2006 Sep;85(9):1621-5. doi: 10.1093/ps/85.9.1621

- Kim, J. G., Lee, E., Kim, S. H., Whang, K. Y., Oh, S., & Imm, J. Y. (2009). Effects of a Lactobacillus casei 393 fermented milk product on bone metabolism in ovariectomised rats. International Dairy Journal, 19(11), 690-695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idairyj.2009.06.009

- Chiang SS, Pan TM. Antiosteoporotic effects of Lactobacillus -fermented soy skim milk on bone mineral density and the microstructure of femoral bone in ovariectomized mice. J Agric Food Chem. 2011 Jul 27;59(14):7734-42. doi: 10.1021/jf2013716.

- Amdekar S, Roy P, Singh V, Kumar A, Singh R, Sharma P. Anti-inflammatory activity of lactobacillus on carrageenan-induced paw edema in male wistar rats. Int J Inflam. 2012;2012:752015. doi: 10.1155/2012/752015

- Tomofuji T, Ekuni D, Azuma T, Irie K, Endo Y, Yamamoto T, Ishikado A, Sato T, Harada K, Suido H, Morita M. Supplementation of broccoli or Bifidobacterium longum-fermented broccoli suppresses serum lipid peroxidation and osteoclast differentiation on alveolar bone surface in rats fed a high-cholesterol diet. Nutr Res. 2012 Apr;32(4):301-7. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2012.03.006.

- Rodrigues FC, Castro AS, Rodrigues VC, Fernandes SA, Fontes EA, de Oliveira TT, Martino HS, de Luces Fortes Ferreira CL. Yacon flour and Bifidobacterium longum modulate bone health in rats. J Med Food. 2012 Jul;15(7):664-70. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2011.0296

- McCabe LR, Irwin R, Schaefer L, Britton RA. Probiotic use decreases intestinal inflammation and increases bone density in healthy male but not female mice. J Cell Physiol. 2013 Aug;228(8):1793-8. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24340

- Britton RA, Irwin R, Quach D, Schaefer L, Zhang J, Lee T, Parameswaran N, McCabe LR. Probiotic L. reuteri treatment prevents bone loss in a menopausal ovariectomized mouse model. J Cell Physiol. 2014 Nov;229(11):1822-30. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24636

- Ohlsson C, Engdahl C, Fåk F, Andersson A, Windahl SH, Farman HH, Movérare-Skrtic S, Islander U, Sjögren K. Probiotics protect mice from ovariectomy-induced cortical bone loss. PLoS One. 2014 Mar 17;9(3):e92368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092368

- Zhang R, Zhou M, Tu Y, Zhang NF, Deng KD, Ma T, Diao QY. Effect of oral administration of probiotics on growth performance, apparent nutrient digestibility and stress-related indicators in Holstein calves. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl). 2016 Feb;100(1):33-8. doi: 10.1111/jpn.12338

- Collins FL, Irwin R, Bierhalter H, Schepper J, Britton RA, Parameswaran N, McCabe LR. Lactobacillus reuteri 6475 Increases Bone Density in Intact Females Only under an Inflammatory Setting. PLoS One. 2016 Apr 8;11(4):e0153180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153180

- Dar HY, Shukla P, Mishra PK, Anupam R, Mondal RK, Tomar GB, Sharma V, Srivastava RK. Lactobacillus acidophilus inhibits bone loss and increases bone heterogeneity in osteoporotic mice via modulating Treg-Th17 cell balance. Bone Rep. 2018 Feb 5;8:46-56. doi: 10.1016/j.bonr.2018.02.001

- Parvaneh M, Karimi G, Jamaluddin R, Ng MH, Zuriati I, Muhammad SI. Lactobacillus helveticus (ATCC 27558) upregulates Runx2 and Bmp2 and modulates bone mineral density in ovariectomy-induced bone loss rats. Clin Interv Aging. 2018 Aug 30;13:1555-1564. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S169223

- Kim WK, Jang YJ, Han DH, Seo B, Park S, Lee CH, Ko G. Administration of Lactobacillus fermentum KBL375 Causes Taxonomic and Functional Changes in Gut Microbiota Leading to Improvement of Atopic Dermatitis. Front Mol Biosci. 2019 Sep 27;6:92. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2019.00092

- Collins FL, Rios-Arce ND, Schepper JD, Jones AD, Schaefer L, Britton RA, McCabe LR, Parameswaran N. Beneficial effects of Lactobacillus reuteri 6475 on bone density in male mice is dependent on lymphocytes. Sci Rep. 2019 Oct 11;9(1):14708. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-51293-8

- Yang F, Wang Y, Zhao S, Wang Y. Lactobacillus plantarum Inoculants Delay Spoilage of High Moisture Alfalfa Silages by Regulating Bacterial Community Composition. Front Microbiol. 2020 Aug 12;11:1989. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01989

- Sojan JM, Raman R, Muller M, Carnevali O, Renn J. Probiotics Enhance Bone Growth and Rescue BMP Inhibition: New Transgenic Zebrafish Lines to Study Bone Health. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Apr 26;23(9):4748. doi: 10.3390/ijms23094748.

- Narva M, Nevala R, Poussa T, Korpela R. The effect of Lactobacillus helveticus fermented milk on acute changes in calcium metabolism in postmenopausal women. Eur J Nutr. 2004 Apr;43(2):61-8. doi: 10.1007/s00394-004-0441-y.

- Jafarnejad S, Shab-Bidar S, Speakman JR, Parastui K, Daneshi-Maskooni M, Djafarian K. Probiotics Reduce the Risk of Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea in Adults (18-64 Years) but Not the Elderly (>65 Years): A Meta-Analysis. Nutr Clin Pract. 2016 Aug;31(4):502-13. doi: 10.1177/0884533616639399

- Lambert MNT, Thybo CB, Lykkeboe S, Rasmussen LM, Frette X, Christensen LP, Jeppesen PB. Combined bioavailable isoflavones and probiotics improve bone status and estrogen metabolism in postmenopausal osteopenic women: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017 Sep;106(3):909-920. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.117.153353

- Nilsson AG, Sundh D, Bäckhed F, Lorentzon M. Lactobacillus reuteri reduces bone loss in older women with low bone mineral density: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, clinical trial. J Intern Med. 2018 Sep;284(3):307-317. doi: 10.1111/joim.12805.

- Takimoto T, Hatanaka M, Hoshino T, Takara T, Tanaka K, Shimizu A, Morita H, Nakamura T. Effect of Bacillus subtilis C-3102 on bone mineral density in healthy postmenopausal Japanese women: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Biosci Microbiota Food Health. 2018;37(4):87-96. doi: 10.12938/bmfh.18-006

- Jansson PA, Curiac D, Lazou Ahrén I, Hansson F, Martinsson Niskanen T, Sjögren K, Ohlsson C. Probiotic treatment using a mix of three Lactobacillus strains for lumbar spine bone loss in postmenopausal women: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet Rheumatol. 2019 Nov;1(3):e154-e162. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(19)30068-2.

- Wang H, Braun C, Murphy EF, Enck P. Bifidobacterium longum 1714™ Strain Modulates Brain Activity of Healthy Volunteers During Social Stress. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019 Jul;114(7):1152-1162. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000203.

- Liu J, Curtis EM, Cooper C, Harvey NC. State of the art in osteoporosis risk assessment and treatment. J Endocrinol Invest. 2019 Oct;42(10):1149-1164. doi: 10.1007/s40618-019-01041-6

- Guo M, Wang H, Xu S, Zhuang Y, An J, Su C, et al.. Alteration in Gut Microbiota Is Associated With Dysregulation of Cytokines and Glucocorticoid Therapy in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Gut Microbes (2020) 11:1758–73. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2020.1768644

- Druart C, Alligier M, Salazar N, Neyrinck AM, Delzenne NM. 2014. Modulation of the gut microbiota by nutrients with prebiotic and probiotic properties. Adv Nutr. 5(5):624s-633s.

- Castaneda M, Strong JM, Alabi DA, Hernandez CJ. 2020. The gut microbiome and bone strength. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 18(6):677-683.

- Lucas S, Omata Y, Hofmann J, Böttcher M, Iljazovic A, Sarter K, Albrecht O, Schulz O, Krishnacoumar B, Krönke G et al. 2018. Short-chain fatty acids regulate systemic bone mass and protect from pathological bone loss. Nat Commun. 9(1):55.

- Anjum N, Maqsood S, Masud T, Ahmad A, Sohail A, Momin A. 2014. Lactobacillus acidophilus: Characterization of the species and application in food production. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 54(9):1241-1251.

- Rizzoli R. 2019. Nutritional influence on bone: Role of gut microbiota. Aging Clin Exp Res. 31(6):743-751.

- Chen C, Dong B, Wang Y, Zhang Q, Wang B, Feng S, Zhu Y. 2020. The role of bacillus acidophilus in osteoporosis and its roles in proliferation and differentiation. J Clin Lab Anal. 34(11):e23471.

- Lin YP, Thibodeaux CH, Peña JA, Ferry GD, Versalovic J. 2008. Probiotic lactobacillus reuteri suppress proinflammatory cytokines via c-jun. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 14(8):1068-1083.

- Hemarajata P, Versalovic J. 2013. Effects of probiotics on gut microbiota: Mechanisms of intestinal immunomodulation and neuromodulation. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 6(1):39-51.

- Malmir H, Ejtahed HS, Soroush AR, Mortazavian AM, Fahimfar N, Ostovar A, Esmaillzadeh A, Larijani B, Hasani-Ranjbar S. Probiotics as a New Regulator for Bone Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021 Aug 2;2021:3582989. doi: 10.1155/2021/3582989.

- Vanitchanont, M.; Vallibhakara, S.A.-O.; Sophonsritsuk, A.; Vallibhakara, O. Effects of Multispecies Probiotic Supplementation on Serum Bone Turnover Markers in Postmenopausal Women with Osteopenia: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2024, 16, 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16030461

- Nilsson AG, Sundh D, Bäckhed F, Lorentzon M. Lactobacillus reuteri reduces bone loss in older women with low bone mineral density: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, clinical trial. J Intern Med. 2018 Sep;284(3):307-317. doi: 10.1111/joim.12805

- Ghanem KZ, Badawy IH, Abdel-Salam AM. 2004. Influence of yoghurt and probiotic yoghurt on the absorption of calcium, magnesium, iron and bone mineralization in rats. Milchwissenschaft 59:472–475.

- Rodrigues FC, Castro AS, Rodrigues VC, Fernandes SA, Fontes EA, de Oliveira TT, Martino HS, de Luces Fortes Ferreira CL. 2012. Yacon flour and Bifidobacterium longum modulate bone health in rats. J Med Food 15:664–670 https://doi.org/10.1089/jmf.2011.0296.

- Moudani, Walid & Shahin, Ahmad & Chakik, Fadi & Rajab, Dima. (2011). Intelligent Predictive Osteoporosis System. International Journal of Computer Applications. 32.